Sister Mary Murderous

Favorite genres are traditional mystery, police procedurals, espionage, Eurocrime, literary fiction and nonfiction history, especially WW2 and Cold War. I write about crime fiction at Read Me Deadly (www.readmedeadly.com)

More of a scholarly biography and study of Middlemarch than the title and description suggest

When I read the title and the book description, I thought this would be a book about Rebecca Mead's experiences and how she related them to George Eliot's life and the lives of Dorothea Brook and the other characters in Mead's beloved Middlemarch. Although that is a theme of the book, it's a minor theme.

The major theme is the life of George Eliot, and how her experiences informed the writing of her greatest novel. We learn about Eliot's girlhood as Mary Anne Evans; her love of scholarship; her rejection of religion and the rift it opened between her and her beloved father; Eliot's relationship with George Lewes and his children; their friends, the Pattersons, and speculation that the Pattersons were the models for Middlemarch's Dorothea Brooke and Casaubon. And, every now and then, we also learn about Rebecca Mead's life and the parallels she sees between it and George Eliot's.

In her note about the book, Mead expresses the hope that she has written a book that can be read by people who haven't read Middlemarch. I have read Middlemarch, and I would say that although this book can be read without having read Middlemarch, I would definitely not recommend it. At the very least, the potential reader should read the Wikipedia entry on the book and get a good grounding in the book's characters and themes first.

One of the reasons I decided to read this book is that it kept popping up everywhere and getting a lot of favorable press. When that happened a couple of months ago with Donna Tartt's The Goldfinch, I gave in and read it and loved it. I decided I should do that with this book and maybe I would get the same result. But I didn't.

While the book was interesting and conveyed Mead's great admiration for George Eliot and Middlemarch, it did it in a sort of detached, scholarly way that left me feeling emotionally distant from the book. I'm not at all sorry I read it and I do feel it enlarged my knowledge of George Eliot and the experiences that went into her writing, but it didn't engage me at a more visceral level.

If the book had been marketed more honestly, I might have appreciated it more.

1

1

One of the story lines is much stronger than the other

We start off in 2004, when we meet newly-minted college graduate Tristan Campbell, who receives a letter from a London firm of solicitors, telling him that he may be heir to the long-unclaimed fortune of Ashley Walsingham--if only Tristan can prove his blood relationship, and soon. The second story thread is Ashley's; his meeting and crash-bang falling in love with Imogen Soames-Andersson just days before he is to report for combat duty in the trenches of World War I France, and his attempt to climb Mount Everest in 1924.

With only two months before Walsingham's fortune will be defaulted to charitable beneficiaries, Tristan searches desperately through archives, abandoned homes, museums and other sites in London, France, Sweden, Germany and Iceland to find evidence that he is related to Imogen, Walsingham's named beneficiary. Tristan picks up a companion along the way named Mireille, and the quest for a fortune fades in importance as he becomes almost obsessed with finding out the history of Imogen and Ashley.

The strongest part of the book is its descriptions of Ashley Walsingham's arduous experiences in the trenches and then while attempting Everest. Justin Go excels at making the reader feel the cold, wet, stink, repulsion, paralyzing fear and, ultimately, numbness that the front-line soldier experienced. Then he takes our breath away on the bleak, frozen mountain, with winds roaring and the visible world reduced to nothing.

All that atmosphere evaporates when the story switches back to Tristan. I've enjoyed quite a few of those biblio/archival detective stories (like Michael Gruber'sThe Book of Air and Shadows, for example) over the years, so I was particularly interested in reading about Tristan's under-the-gun documentary search all over Europe. It followed some of the standard formula, like picking up a companion along the way to add some romance, but it lacked drama and emotion.

It was hard to get much of a feel for Tristan and his companion, Mireille. They seemed like pale imitations of Ashley and Imogen. The quest itself was lacking for several reasons. Right off the bat, the restrictions that the solicitors put on Tristan seemed dubious. Tristan's searches were haphazard, and dumb luck and happenstance led him to most of his finds.

If your primary interest in the book is because you like literary detective stories, I think you'll find this one may leave you flat. But if you are attracted more by a World War I and Everest adventure/romance novel, then this should be worth your while.

Note: Thanks to the publisher and Amazon's Vine program for an advance reviewing copy of the book.

As gripping as any espionage thriller or courtroom drama

I knew the basics of the Dreyfus Affair, but what I didn't know is that the most interesting parts of the story happen when Captain Albert Dreyfus is offstage. First off, I should say that although this book is classified as fiction, author Robert Harris tells us that his goal is to use the techniques of a novel to retell the true story of the Dreyfus Affair. The characters and the events are real.

The central figure in this very dramatic story is Colonel Georges Picquart. As someone who had become acquainted with Dreyfus some years earlier when Dreyfus was a young officer training at the military college where Picquart taught. Picquart was present at Dreyfus's arrest by the army on charges of passing secret military information to German agents. Picquart had no trouble believing in Dreyfus's guilt, in part because Picquart was an anti-Semite, as most soldiers were.

Dreyfus was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment in terrible conditions on Devil's Island, 8,000 miles from France. He left behind a young wife, two small children and other family members who were determined to use the family's considerable wealth to exonerate Dreyfus.

None of this was of any particular interest to Picquart, until he was assigned, shortly after Dreyfus's conviction, to become the chief of the military's secret intelligence bureau, called the "Statistical Section." Almost by accident, Picquart soon discovered that the evidence against Dreyfus was almost nonexistent, but that there was good evidence that the real traitor was a womanizer, gambler and cheat, Major Walsin Esterhazy.

This is the set-up to what becomes a story that would be too unbelievable as an original piece of fiction. But it's only too plausible today, when we've become jaded by seeing how, all over the world, political, military, religious forces and their associates often place their own institutional interests above quaint concepts like truth, honor and justice. Dreyfus, Picquart and other individuals were just pawns in a chess game for the various institutions' visions of the future of France and its military. But chess game is putting it too politely. This was a game of double-dealing, dirty tricks and possibly even murder.

The late 19th century was a time of ferment in France. The French Republic was in its infancy and besieged by monarchists, the Catholic Church and the military on one side, and socialists and anti-clericalists on the other. The Army, having suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of Germany in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, was rigid, hidebound and reactionary. The warring sides seized on the Dreyfus Affair to carry their messages, inciting a press war, whipping up the populace to riotous demonstrations and bringing the country to the brink of civil war.

Robert Harris, probably best known for his masterful novel of alternate history, Fatherland, has brought history vividly to life here. He slowly and deliberately establishes his story, but by about halfway through, events are rolling forward like a steam engine at peak running speed. Even if you already know exactly how the historical events unfolded, I think you'll find it as hard as I did to put the book down.

Harris's character portrait of Picquart paints him as more attractive than he probably was in real life. Harris doesn't make him an out-and-out hero, but he underplays Picquart's anti-Semitism as much as possible. He emphasizes that Picquart is an anti-clerical. I'm not at all sure there is much evidence for Picquart's anti-clericalism, but it helps illustrate the larger forces at work behind the Dreyfus case. And, although we don't get inside Picquart's heart and mind deeply, Harris so well describes the effect of him on the endless inquiries, trials and re-trials: "I am the founder of the school of Dreyfus studies: its leading scholar, its star professor--there is nothing I can be asked about my specialist field that I do now know: every letter and telegram, every personality, every forgery, every lie."

Harris also makes several of the Army officers almost comic-opera villains, especially Major Armand Mercier du Paty de Clam. Who knows, though; that may be accurate. Mercier du Paty de Clam (amazing name, isn't it?) was the officer principally responsible for identifying the officer who was passing secrets to the Germans. His choice of Dreyfus as the culprit seems to have been motivated by little more than Mercier du Paty de Clam's rabid anti-Semitism. And the apple didn't fall far from the tree. Mercier du Paty de Clam's son, Charles Armand Auguste Ferdinand Mercier du Paty de Clam became Commissioner General for Jewish Affairs in the Nazi collaborationist Vichy government during World War II.

I wish Harris could have worked in more detail about the political ferment behind the events described in the book, but I recognize what a challenge that would have been. Despite not having that stronger historical foundation, and some possible oversimplification of the characters, this was a completely riveting read. It's the kind of book that will stay in my mind for hours or days to come.

A refreshingly different and entertaining coming-of-age story of two strong young women--but definitely not for everyone

Sophie Diehl is a graduate of Yale Law School and an associate practicing criminal law with a small but prestigious firm in the fictional town of New Salem in the also fictional state of Narragansett. When Mia Meiklejohn, the daughter of one of the firm's most important clients, is served with divorce papers by her husband, Dr. Daniel Durkheim, at a time when the firm's experts aren't around, managing partner David Greaves corrals Sophie and has her take on Mia's initial interview. Mia decides she likes Sophie's style and asks for her to continue representing her. Since a rich and powerful client's request is taken as an unrefusable demand, Sophie will spend all of 1999 learning that marital law might just be at least as down and dirty as criminal law.

Sophie's "legal file" is the vehicle for this novel. It includes formal documents, such as legal memoranda, court filings, legal cases, settlement offers, and financial records, and also informal papers like personal letters among Mia, her daughter Jane, her father, Daniel, Daniel's (first) ex-wife and Daniel's current mistress, emails between Sophie and her best friend Maggie, and unclassifiable internal memos between Sophie and David Greaves in which she talks about the law, movies and her personal life.

Wikipedia says that the epistolary form (telling a story through a series of documents):

. . . can add greater realism to a story, because it mimics the workings of real life. It is thus able to demonstrate differing points of view without recourse to the device of an omniscient narrator.

The form of this novel does provide a you-are-there feel. I enjoyed never knowing when I turned the page whether I'd next be reading a handwritten nastygram from Mia to Daniel; a formal (but razor sharp) settlement offer letter from Sophie to Daniel's shyster lawyer; a gossipy email from Sophie to Maggie about Sophie's dating life, her sometimes difficult relationships with her parents or her in-office nemesis, Fiona; a newspaper article; the text of a precedent-setting court opinion.

Although the title is The Divorce Papers, and that's the form the novel takes, this is actually the story of Sophie's personal and professional coming of age. Sophie is in her late 20s and making the transition from daughter to independent adult, from legal ingenue to confident practitioner, from dating failure to woman in a relationship. She is an appealing young woman and comes across in the book as something like a smarter and more adroit Bridget Jones.

But it's a secondary character who steals every scene she's in. Mia is a real pistol. Her husband, Daniel, may be one of the country's foremost experts in pediatric oncology, but he and his lawyer walk into a human buzzsaw when they cross her. A woman who downshifted her journalism career to move to New Salem for her husband's practice and to raise their daughter, Jane, Mia finds that the electric shock of being served divorce papers has galvanized her in every aspect of her life--and taken any governor off her tongue that she might have had in the past.

While I thought this was a delightfully different novel, with many engaging characters--as well as some love-to-hate villains--it won't be for everyone. Some people just don't like epistolary novels, period. And, in this case, many of the documents are legal forms and financial documents. Though the author avoids legalisms as much as reasonably feasible, some readers will be unwilling to read these documents, even fictional documents, for pleasure.

Most of the characters are privileged, sophisticated and highly educated, which leads to a style of writing that is more formal and self-consciously intellectual than in a typical novel. While this seemed to me to be appropriate to the characters and their setting, some readers may find it affected and off-putting.

If you're a lawyer, or you know lawyers, then this book might be of particular interest. Susan Rieger must know some law-firm lawyers herself, because her writing about internal firm issues and how battles are waged within a firm is lively and has a realistic feel. At the same time, she does make a number of errors about law-firm practice (which I won't go into here). I didn't think they got in the way of the story, but if you're a stickler you may not agree.

My (non-precedential ;-} ) opinion is that this is an entertaining coming-of-age novel about two strong female characters, and a welcome addition to the category of epistolary novels.

Note: Thanks to the publisher and Amazon's Vine program for an advance reviewing copy of the book.

1

1

A Dangerous Deceit

World War I and its aftermath have been fertile ground for mysteries set in the UK, with Charles Todd and Jacqueline Winspear being just two authors who have tilled that field. Marjorie Eccles goes back a little further for her inspiration: The Second Boer War of 1899-1902.

World War I and its aftermath have been fertile ground for mysteries set in the UK, with Charles Todd and Jacqueline Winspear being just two authors who have tilled that field. Marjorie Eccles goes back a little further for her inspiration: The Second Boer War of 1899-1902.In this English-village mystery, set in Folbury, Margaret Rees-Talbot is engaged to clergyman Symon Scroope and, while she is happily in love, her happiness is tempered by her grief over her beloved father's recent death. It's more than grief, though, because there is some concern that Osbert Rees-Talbot, who lost an arm in the Boer War, may actually have killed himself, rather than died accidentally. But what could have made the man whom Marjorie idolized take his own life?

Meanwhile, in the village, DI Reardon and DS Joe Gilmour are involved in the investigation of another apparent accidental death. This one, though, is quickly determined to be murder. Foundry owner Arthur Aston was a crude, rough and aggressive man who'd been Osbert Rees-Talbot's batman (personal servant) during the war. He had no shortage of enemies including, possibly, Rees-Talbot and his family, whom witnesses claim they heard arguing with Aston. And is there a connection between Aston's murder and that of the unidentified man whose months-dead body was found in the wood. In particular, is there a South African connection, since all three recent deaths have that country in common?

This is a Golden Age type of mystery in its setting and atmosphere. I wouldn't call it a fair-play or puzzle style of mystery, though. While the police detectives are featured, we don't closely follow their investigation to pick up clues and attempt to solve the crime(s) along with them. Instead, the plot is more languid, and the solution plays out in a storytelling fashion.

I would have liked to get a stronger feeling for some of the characters in the story, especially Margaret, Symon, and the police detectives. Still, it was an engaging read and I would recommend it to anybody looking for a traditional mystery. I would also welcome more books featuring Reardon and Gilmour.

Note: I received a free Netgalley review copy of this book.

1

1

Even though I've read hundreds of novels and history books about the Holocaust, Wendy Lower's study was a revelation. In a way, it shouldn't have been. Having read a lot about the Einsatzgruppen (mobile killing squads who murdered Jews, Gypsies, Slavs and others in the east, to make room for Germany's intended rural paradise), euthanasia programs, Gestapo offices, occupation bureaucracies and other elements of the Nazi operations, I knew that there were many nurses, secretaries and wives who were part of or associated with those operations.

Even though I've read hundreds of novels and history books about the Holocaust, Wendy Lower's study was a revelation. In a way, it shouldn't have been. Having read a lot about the Einsatzgruppen (mobile killing squads who murdered Jews, Gypsies, Slavs and others in the east, to make room for Germany's intended rural paradise), euthanasia programs, Gestapo offices, occupation bureaucracies and other elements of the Nazi operations, I knew that there were many nurses, secretaries and wives who were part of or associated with those operations.But this knowledge stayed in the back of my mind. I never really considered that this meant there were hundreds of thousands of German women who euthanized people on a regular basis, and who pushed the reams of paper dispossessing the Nazis' targets and ordering and reporting on mass murder.. What I really didn't know at all was the level of direct involvement in dispossessing Nazi targets and actually killing them by women sent to work in the east (or who accompanied men sent to the east).

You will not read much of anything in this book about sadistic Nazi prison guards in this book. Lower acknowledges that's what most people think of when the subject of women involved in the Nazi killing machine comes up. But her point is that there were many, many more women who were involved in the genocide. Middle-class and upper-class women felt it was their duty to work in the genocidal bureaucracy. What's more, many bought into the propaganda about the opportunities in the east and headed there with ambitions of achieving a better life.

How could this happen? Lower shows us that most of these women were young; in their twenties. They'd been indoctrinated into the Nazis' racial mindset since their early youth. Women were trained in shooting and had it drummed into their heads that the life of the Aryan nation absolutely depended on eradicating the eternal Jewish and Bolshevik enemies, and subjugating the Slavs. This is an eye-opening illustration of how training could turn significant numbers of people, including women, into uncaring "desk killers" at best, and cold-blooded murderers at worst.

The horror of what Germans did during the war never leaves us, but when Lower throws a light on how the deadly Nazi ideology was able to destroy the humanity of so many women, it intensifies our dismay. It's even more disheartening to learn that even after the war ended, so many of these women never came to terms with their wrongs. They continued to feel that the Jews were a threat and that any punishment the German perpetrators faced was simply revenge persecution. They even had the gall to claim that they were being treated worse than the Jews had been.

The narrative of this book is relatively short and readable for history, making it easily accessible, but it is supported by extensive notes for serious students of history.

The Windsor Faction: A Novel

I'm an sucker for World War II history and fiction, and if it's alternative history, then I lose all resistance whatsoever. Robert Harris's Fatherland, Stephen Fry's Making History, Jo Walton's Small Change trilogy, Kate Atkinson's Life After Life; they're just a few of the books in this sub- sub-genre I've enjoyed, and I have C. J. Sansom's Dominion waiting.

I'm an sucker for World War II history and fiction, and if it's alternative history, then I lose all resistance whatsoever. Robert Harris's Fatherland, Stephen Fry's Making History, Jo Walton's Small Change trilogy, Kate Atkinson's Life After Life; they're just a few of the books in this sub- sub-genre I've enjoyed, and I have C. J. Sansom's Dominion waiting.Of course, then, when I hear about a book that imagines Edward VIII doesn't abdicate and is on the throne during the first year of the war (the period known as the Phoney War), I'm all in. You'll remember that Edward VIII, like many of his aristocratic pals, thought the Nazis were just swell and should be allowed free reign in central Europe. It makes for a compelling premise, then, to imagine the what-ifs of Edward VIII still wearing the crown.

The "Windsor Faction" is a group of right-wingers, including politicians, civil servants, journalists and military officers who are certain the Nazis can be dealt with civilly, and there is no good reason to go to war over the Slavs––and certainly not over the Jews. Many of the Faction's members––and a distressingly high number of ordinary Britons––have bought into the notion that this is a war engineered by Jews, for their financial benefit.

Author D. J. Taylor presents Edward VIII more subtly than I expected. He isn't written as the empty-headed socialite with anti-Semite proclivities who is often presented in literature and history. He is a World War I veteran and wants to avoid the senseless slaughter of that war. He hopes that actively engaging the Germans in peace talks will prevent the Phoney War from heating up into the real thing, with the price being, at most, giving Germany free reign in countries where there are large ethnic German populations, in exchange for their promise to treat non-Aryans humanely.

Taylor tells the story from several points of view, including the King, journalist and gay bon vivant Beverley Nichols, a shop clerk who passes messages for the Faction, an MI-5 agent, and Cynthia Kirkpatrick, a young woman just returned to England from several years living with her family in what was then the British colony of Ceylon. We follow Cynthia's reintroduction to London life, employment at a literary magazine, and acquaintance with characters who take different positions on the war. She is ambivalent, but she will be forced to choose, and this is what gives the story its thriller plot.

As with most historical novels, The Windsor Faction includes a mix of real and imagined characters. Here, though, Taylor takes the daring step of placing several real figures in the Faction. Captain Ramsay is based on Archibald Ramsay, the MP who led the "Right Club," a Fascist organization on which the Faction is based. Beverley Nichols was a real-life journalist, social gadfly and pacifist who, in The Windsor Faction, is represented by fictional journal entries detailing his helping the King insert peace propaganda into the monarch's traditional Christmas Day broadcast––along with asides about Noël Coward and allusions to Nichols's assignations with young men who make a habit of lifting his belongings. Tyler Kent was an American cipher clerk at the American Embassy who, in this novel, is part of the Faction and regularly conspiring with Captain Ramsay.

While I found the novel's ideas compelling, and its depiction of London during the Phoney War evocative, there are some weak points in the execution. The most significant is the Cynthia character. She's so ineffectual that I wanted to give her a kick in the pants. She has the puzzling habit of sleeping with men she doesn't like, apparently just because they want her to. I didn't expect her to turn into some kind of superhero in the thriller plot, but she was so passive most of the time that it was frustrating. While someone in her position was a good choice of protagonist, her weak-willed character was hard to respect or identify with.

The writing style is a bit uneven as well. There is some beautiful and imaginative writing, but then there are some real clunkers and oddities, like comparing things to gravy (of all things) so often throughout the book that it was distracting. The book is also very talky for about two-thirds its length, when it suddenly turns into a thriller––one that strains credulity at times.

The book is also likely to present some challenges to American readers, unless they have a depth of knowledge not only of the wartime history of England and its political figures, but also of cultural personalities. Most history buffs will know about Edward VIII, Churchill, Lord Halifax and a number of other less prominent characters in the story. But I doubt many Americans will have any idea who Archibald Ramsay, Beverley Nichols and Tyler Kent were, and they are major characters. While I don't think that is a huge problem, it makes for a layer of meaning and nuance that will be missing.

With these caveats, I would recommend The Windsor Faction to readers with a strong interest in World War II alternate history novels. Despite its faults, Taylor's evocation of London's atmosphere and the depiction of its citizens during the Phoney War is compelling.

Note: I received a free review copy of this book.

World War II, which historian Max Hastings called "the greatest and most terrible event in human history," will never fail to be a subject that fascinates historians, novelists and readers. Lately, though, it seems that the immediate aftermath of the war has caught writers' interest. Just off the top of my head, I can think of these books: Tony Judt's Postwar, William I. Hitchcock's The Bitter Road to Freedom: A New History of the Liberation of Europe, Ian Buruma's Year Zero: A History of 1945, and, on the fiction side, John Lawton's wonderful Then We Take Berlin.

World War II, which historian Max Hastings called "the greatest and most terrible event in human history," will never fail to be a subject that fascinates historians, novelists and readers. Lately, though, it seems that the immediate aftermath of the war has caught writers' interest. Just off the top of my head, I can think of these books: Tony Judt's Postwar, William I. Hitchcock's The Bitter Road to Freedom: A New History of the Liberation of Europe, Ian Buruma's Year Zero: A History of 1945, and, on the fiction side, John Lawton's wonderful Then We Take Berlin.Rhidian Brook joins this group with his new novel, Aftermath, set in Hamburg. Hamburg, once a vital port city, in 1946 is another wrecked city in the German landscape, with bodies still buried under mounds of bombed-out husks of buildings, defeated Germans devoting all of their waning energy to finding food and cigarettes whatever way they can, and the conqueror Allies trying to figure out how to build a foundation for a new country on this blasted wasteland with these fragile people.

British officer Colonel Lewis Morgan is assigned a large, palatial house, but he is still enough of an idealist that he doesn't want to have its current residents turned out. And so, when his wife Rachael arrives, with their son Edmund, she finds that they are sharing living quarters with Stefan Lubert, an architect, and his daughter, 15-year-old Freda. For Rachael, this is discomfiting. The Morgans' oldest son was killed in her presence by a stray bomb and she is less kindly disposed toward Germans. Still, she is emotionally affected by seeing that so many Germans also lost their lives in bombing and she accepts the presence of the Luberts in the house––so long as they stick to their quarters.

There are parallels between the Morgans and the Luberts. Frau Lubert was killed in a British bombing raid, which leaves Stefan Lubert mourning and Freda filled with hostility. It seems that Rachael and Stefan almost need each other, and that Freda and Edmund's need to coexist in the house also plays out as a parallel to the rocky road to reconciliation between the Germans and Allies.

While Brook paints an evocative picture of war-ruined Hamburg, he is less successful with his characters. Maybe it's that famous British reserve, but I never got much of a feel for Lewis, Rachael or Stefan. That improved as the book neared its end, but by then it was too little, too late.

Brook's writing is often beautiful, but there are also some awfully clunky moments, such as when he uses the language of today, not the 1940s. The dialog used for the street kids is just plain bizarre; it sounds like what Ring Lardner might have used for the characters in Guys and Dolls if he'd been German.

There is also a film of this story in the works, and I wouldn't be surprised if it ends up working better than the book. The scenery should be striking, acting skills may make up for some of the character deficiencies on the page, and we can hope that the awkward places in the novel's writing will be absent in the film's script. In the meantime, though, if you're interested in a crackerjack story of postwar Germany, I recommend John Lawton's new Then We Take Berlin.

The Tenth Witness

I've lost count of how many novels I've read about the fingers of the ugly World War II past reaching into the present. It's a challenge to make a fresh story on this theme, but Leonard Rosen's The Tenth Witness shows he is more than up to the task.

I've lost count of how many novels I've read about the fingers of the ugly World War II past reaching into the present. It's a challenge to make a fresh story on this theme, but Leonard Rosen's The Tenth Witness shows he is more than up to the task.The Tenth Witness is a prequel to Rosen's impressive and original first Henri Poincaré novel, All Cry Chaos. Most of the action in The Tenth Witness takes place in the late 1970s, before Henri has become an Interpol agent. Henri is an engineer, and he and his partner, Alec Chin, have just landed an exciting project: on behalf of Lloyd's of London, they've built a platform from which they hope to recover the 18th-century wreck of the Lutine, a ship that went down off the Dutch coast, laden with gold bars.

While out hiking, Alec meets Liesl Kraus, and their attraction is immediate. Liesl turns out to be a very wealthy young woman, the daughter of Otto Kraus, founder of Kraus Steel. Henri is soon introduced to Liesl's family, including her charming brother, Anselm, who now runs the firm's operations, and her uncle, Viktor Schmidt, whose bluff heartiness feels to Henri as if its hiding something more menacing.

Henri, who has an honorary uncle Isaac who was a Jewish Holocaust survivor, is curious and cautious about the Kraus family, especially since Anselm and Viktor seem eager for Henri to become involved in some of their overseas businesses. Henri learns that Otto Kraus was a member of the Nazi Party and produced steel for the German war effort, with production fueled by slave labor. After Germany lost the war, Otto had a get-out-of-jail-free card, though: an affidavit, signed by 10 Jewish workers at Kraus Steel, swearing that Kraus had saved lives of the slave laborers; a veritable Oskar Schindler.

When hints surface that the whole Kraus-as-Schindler story might not be the real deal, Henri's love for his adoptive uncle compels him to try to unearth the truth, whatever the cost to himself, his career and his relationship with Liesl. The story really takes off at this point, with Alec traveling around the world gathering intelligence. Henri spends almost as much time slogging through archival documents, and Rosen's writing makes that part of the search every bit as tense and compelling as the globe trotting.

Henri's work and research take him to facilities in the third world where workers who are desperate for any kind of employment are treated only marginally better than the Nazi slave laborers, and to countries where individual freedoms and lives are sacrificed in the name of security and progress. Without being at all sanctimonious, Rosen makes us look at the situational ethics so many used during the Nazi era and ask ourselves if we are so sure we'd have done the right thing, not the expedient thing––and if the choices we make today can stand up to close scrutiny.

As with All Cry Chaos, there is so much going on in this novel; murder, romance, science and technology, a chase after Nazis, and the quest for a gold-laden shipwreck. The plotting is intricate but fast-paced, the storytelling lean but with plenty of food for thought and emotion.

Leonard Rosen has created an appealing and complex protagonist in Henri Poincaré, and his novels offer far more than the usual thriller or whodunnit. If you haven't read them yet, pick one and see for yourself.

Note: I received a free review copy of this book.

As meteorological summer draws to a close, I wanted to read a summer mystery. And what's more summery than a story set in the south of France? In this case, we're in an unusual location for crime fiction: Perpignan, way down in France's Mediterranean south, almost to Spain.

As meteorological summer draws to a close, I wanted to read a summer mystery. And what's more summery than a story set in the south of France? In this case, we're in an unusual location for crime fiction: Perpignan, way down in France's Mediterranean south, almost to Spain.It's another warm July in Perpignan, and police inspector Gilles Sebag is adjusting to changes at home. His teenage daughter and son are both away for the month, and he and his beautiful wife, Clare, are getting a taste of what it will soon be like to be full-time empty nesters. Gilles is looking forward to spending more time alone with Clare, whom he adores even more than when they fell in love at university, but he wonders if she feels the same. Is she lying to him about where she goes when he's busy at work in the evenings? Could she even be having an affair?

At work, Gilles seems to be such an astute and well-respected detective that we wonder why he's not higher-ranked. That's quickly explained. When his second child was born, Gilles took advantage of France's then-new parental-leave law and spent three years working part-time. Nothing was ever said to his face, but it was clear that this didn't go over well in the macho police world. Gilles never received any further advancement. That was alright with him, though. He just wanted to be left alone and allowed to do his job.

Now, two new cases land in Gilles's lap. A Catalan taxi driver, José Lopez, has been reported missing by his wife, and the force also receives a report of a missing young woman--a Dutch tourist named Ingrid. Are the two disappearances connected? And what of the enterprising journalist who livens up the summer torpor with a sensational story that the missing Ingrid is part of a series of attacks on beautiful young Dutch female tourists?

Author Philippe Georget is former TV news anchorman who now lives with his family in Perpignan. This is his debut novel and is a welcome introduction to an appealing new protagonist. Gilles is a thoughtful, intelligent, sensitive guy. Someone you'd like to get to know. His character and devotion to his family make a refreshing change from the usual angst-ridden misfit model (though I enjoy a few of those as well). But that's not to say that Gilles is some conventional Father Knows Best type. We know right away that he's different when we read that he bucked the cultural norm by being a half-time stay-at-home dad. Also, his musings on marriage and his children are very different from what you might expect, and made me hope to learn more about Gilles and Clare in future books.

The Perpignan setting was a bonus. I was somewhat familiar with the city from reading World War II history, because it was so often a meeting place from which refugees and downed Allied pilots escaped France with the aid of guides, who took them off by boat or over the Pyrenees to Spain. Perpignan's World War II history plays no part in this book, though. But we do get a real feel for the summer heat, the beauty of the Rousillon region and the Catalan flavor that mixes with the French. The owner of Gilles's favorite coffee shop is Catalan and Gilles works on his Catalan by conversing with him. I enjoyed learning a little about the dialect this way.

Although this book is part of the publisher's World Noir collection, and the cover blurb calls it French noir, I wouldn't call it noir at all. There are at least a dozen definitions of noir, it's true, but the general consensus is that noir is cynical, fatalistic, with a protagonist who is no hero. In noir, the atmosphere of moral ambiguity is usually thick as a London fog. This book does have a cynical tone at times, and there's a slight mist of moral ambiguity about marriage, but otherwise the story doesn't tick any of the rest of the noir boxes. Gilles is a good guy with a clear agenda to rescue the girl and get the bad guys. I'll confess that I'm not much of a fan of noir, so the fact that this isn't actually noir was a plus for me. But I think even noir fans can still enjoy this book, as long as they don't have expectations that it will fall into that genre.

Oh, finally, about that title. If you read the book, maybe you can tell me what it has to do with the story!

This is a collection of six short stories, each of which stands on its own, though there are some connections between them, and some characters are present in each story. The protagonist is, of course, Sidney Chambers, a Church of England canon in Grantchester, a bucolic village close to Cambridge University. Sidney's sideline is criminal investigation, via his friendship with Cambridgeshire policeman Geordie Keating.

This is a collection of six short stories, each of which stands on its own, though there are some connections between them, and some characters are present in each story. The protagonist is, of course, Sidney Chambers, a Church of England canon in Grantchester, a bucolic village close to Cambridge University. Sidney's sideline is criminal investigation, via his friendship with Cambridgeshire policeman Geordie Keating.Sidney is a mild-mannered man, but there is some spice to his life. He has two women in his life: Amanda, his longtime close friend, and Hildegarde, the German widow who he met in the first volume in this series, when her husband was murdered. In this volume, the stories range from the murder of a Muslim grocer to a close shave for Sidney when he visits Hildegarde in Germany just as the Iron Curtain is ringing down.

Author James Runcie is the son of Robert Runcie, the Archbishop of Canterbury in the 1980s, so he comes by his interest in churchmen honestly. In the website about the Sidney Chambers series, he writes that he plans to have six novels in the series, beginning in 1953 and ending in 1978, writing about a period in which there were vast changes in English society.

Runcie's strong suit is his ability to evoke the feel of the village and the university in the 1950s, so soon after the war's end. The book should be a rewarding experience for those who reading for atmosphere and storytelling. The avid mystery reader may be less pleased, because the crimes tend to be solved in a burst of exposition. There isn't the seeding of clues that allows the careful reader to figure out the whodunnit.

Note about the audiobook: Avoid the audiobook! The reader, Peter Wickham, is terrible at women's voices. In particular, he makes Amanda sound like a little old woman, when she's supposed to be a wealthy young society woman.

Hitler often said that Germany and England were natural allies, being fellow "Aryans" and all. He was peeved, to say the least, when England finally declared war after Germany invaded Poland, and greatly annoyed when the milquetoast-y Chamberlain was replaced by the bellicose Winston Churchill. Early in the war, Hitler has plans to invade England and, in Orders From Berlin, his minion, Reinhard Heydrich, has planted a mole in Britain's MI6 whose mission is to mislead the English about Germany's plans.

Hitler often said that Germany and England were natural allies, being fellow "Aryans" and all. He was peeved, to say the least, when England finally declared war after Germany invaded Poland, and greatly annoyed when the milquetoast-y Chamberlain was replaced by the bellicose Winston Churchill. Early in the war, Hitler has plans to invade England and, in Orders From Berlin, his minion, Reinhard Heydrich, has planted a mole in Britain's MI6 whose mission is to mislead the English about Germany's plans.We're told right from the get-go that the mole is a man named Seaforth, and that his disinformation campaign is going so well that he's being invited to brief Churchill with only his immediate superior, Thorn, present. That gives Heydrich an idea: have Seaforth assassinate Churchill at one of these briefings. Thorn has been suspicious of Seaforth all along, but the MI6 chief, "C," is so in love with Seaforth's (dis)information that he won't hear a word against him.

When Thorn's former mentor and retired MI6 chief, Albert Morrison, is murdered shortly after Thorn has consulted him about a strange message intercepted from Germany, Thorn's suspicions are heightened, but C is recalcitrant. The police investigation is conducted by Inspector Quaid and Detective Sergeant Trave. Quaid is convinced that Morrison was killed by his son-in-law, the smarmy Dr. Brive, but Trave very much doubts it. He thinks it's a more complex case than Quaid wants to believe.

This is a straight-ahead historical thriller that moves along briskly and is wrapped up in just over 300 pages. It was interesting enough, but if you're going to reveal the bad guy right from the start––in other words, if the book isn't a whodunnit––then more complexity in the howdunnit/whydunnit would have been welcome. The Quaid/Trave duo is similar to the C/Thorn team, in that the boss seems never to have heard that some things really are too good to be true, and stands in the way of his junior's attempts to conduct a thorough investigation. The pairs and their dynamic were so similar that it felt like lazy writing.

For me, a no-better-than-average read.

Paris in the Jazz Age is a terrific hook for a mystery, and Laurie R. King gives us many of the big names (Man Ray, Ernest Hemingway, Josephine Baker, just to name a few) who added extra glow to the City of Light in the 1920s. She also includes plenty of descriptions of Paris's streets and haunts as well as French food and dialog. All this is to the good.

Paris in the Jazz Age is a terrific hook for a mystery, and Laurie R. King gives us many of the big names (Man Ray, Ernest Hemingway, Josephine Baker, just to name a few) who added extra glow to the City of Light in the 1920s. She also includes plenty of descriptions of Paris's streets and haunts as well as French food and dialog. All this is to the good.Where things go wrong is with the characters. This is not part of the Sherlock Holmes and Mary Russell series. Instead, it features the characters King introduced in her 2007 book, Touchstone. The protagonist is an American private detective named Harris Stuyvesant, who is trying to find a young American woman named Pip who had been living it up in the artistic and expatriate community before she seemingly dropped off the face of the earth.

The Stuyvesant character never comes to life, nor do any of the book's other characters. Stuyvesant was just an empty suit running around a city both glittering and menacing. The two other characters from Touchstone appear briefly at the beginning and then again only much later in the book. If you read this book without having first read Touchstone, you may well feel at a loss about these characters.

Stuyvesant's search for Pip leads him into the horror of a deranged and perverted mind. For me, the crazed killer theme in mystery has been overdone and it takes real invention to make it feel fresh and interesting. Unfortunately, that's not the case here. Between the weak characters and the distasteful (to me, at least) murder plot, the book was a disappointment that no amount of evocative atmosphere could make up for.

1

1

John Lawton is on my top-5 list of contemporary authors, so I was excited when I heard he had created a new protagonist, John Wilfrid Holderness. That sounds like a posh name, but he's known by most people as Joe Wilderness, which is a much better fit.

John Lawton is on my top-5 list of contemporary authors, so I was excited when I heard he had created a new protagonist, John Wilfrid Holderness. That sounds like a posh name, but he's known by most people as Joe Wilderness, which is a much better fit.Joe is a London East End wide boy, a chancer who lives on his wits and guile. That's all the more true when his mother is killed in the Blitz, found dead ensconced on a barstool with her gin still sitting in front of her. Joe's grandfather Abner moves Joe into an attic room at his place in Whitechapel, where Abner lives with his longtime girlfriend (and sometime prostitute) Merle.

Abner teaches Joe everything he knows about burglary and safe-cracking. Joe is a quick study, not just about crime, but books, and observing people. Just because he's smart doesn't mean Joe is lucky, though. Just when all the soldiers and sailors are returning home from World War II, Joe is drafted. He's about to be tossed into the punishment cells for insubordination when he's plucked out by Lieutenant Colonel Burne-Jones, who's seen Joe's IQ score. Burne-Jones sends Joe off to Cambridge to learn Russian and German, and to London for personal tutoring in languages, politics and history.

Of course, Burne-Jones is training Joe to work in military intelligence, but you already figured that out. Off Joe goes to Berlin in 1946. What an amazing place for a wide boy. "It was love at first sight. He and Berlin were made for each other. He took to it like a rat to a sewer." In between intelligence jobs for Burne-Jones, Joe can't resist increasing the stakes in his black market game, which means making ever larger and more dangerous deals, deals that involve crossing over to the Russian sector.

But for Joe, it's not all about sussing out former Nazi bigwigs and scientists by day and smuggling by night. At one of Berlin's nightclubs, famous in the Weimar era for using tabletop telephones and pneumatic tubes so that strangers could propose assignations, Joe meets Christina Helene von Raeder Burckhardt, known by the Brits and Americans as Nell Breakheart. Not because she actually breaks hearts, but because she's so beautiful, inside and out, that they're lining up in hopes of getting their hearts broken. And wouldn't you know, she chooses Joe.

In language so vivid you can see it all in your mind, Lawton recreates postwar Berlin, with its ruined buildings, squalid living quarters created in cellars or apartments with shorn-off walls, crews of women who earn rations by clearing rubble in bucket lines, dirty kids harassing servicemen from the US, Britain, France and Russia for candy bars, the stink of open sewers, fear and despair, and the sweeter scents of money, graft and opportunity. I read a ton of WW2 historical novels and I can't think of another one that does it better.

But the novel isn't all postwar Berlin. It's bookended by the stories of Joe and Nell in the summer of 1963. You know, the summer JFK made his famous visit to Berlin. If there is some of the 1963 plot that is not quite up to snuff (and there is), that takes up a very small proportion of what is a dazzlingly inventive and layered story, packed with fully dimensional characters–––several of whom Lawton fans will recognize from the Frederick Troy novels.

I've often wondered why John Lawton hasn't gained the recognition I firmly believe he deserves. I've come to think it might be because of the book world's compulsion to categorize books and authors into easy genres and sub-genres. Lawton's books are most often classified as mystery and espionage, but neither is accurate. As Lawton once commented, they are "historical, political thrillers with a big splash of romance, wrapped up in a coat of noir." The noir comes in because, as you might have suspected reading about Joe Wilderness, John Lawton likes to write about people on the edge, living in a world of shadowy morality.

If you enjoy authors like Ian McEwan, Philip Kerr, Sebastian Faulks and William Boyd, give this book a try, along with his other novels, especially his haunting 2011 title, A Lily of the Field.

Note: I received a free review e-galley from Netgalley.

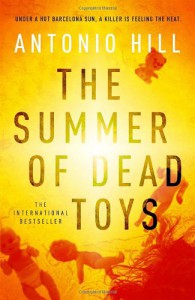

In this debut novel by translator-by-trade Antonio Hill, Barcelona police Inspector Hector Salgado has just returned from his native Buenos Aires and a month-long forced leave. Hector was ordered to make himself scarce for long enough for the bad press to die down from a scandal born of Hector's savage beating of Doctor Omar, a creepy voodoo figure in a human trafficking case.

In this debut novel by translator-by-trade Antonio Hill, Barcelona police Inspector Hector Salgado has just returned from his native Buenos Aires and a month-long forced leave. Hector was ordered to make himself scarce for long enough for the bad press to die down from a scandal born of Hector's savage beating of Doctor Omar, a creepy voodoo figure in a human trafficking case.Though Hector has returned to the force, his boss, Superintendent Savall, orders him to stay in the background, and gives him an inconsequential assignment. A rich young man, Marc, from a wealthy and influential family fell or jumped from a window and was killed, and the young man's mother has been harassing the police, insisting on an investigation. Hector is the perfect choice for the job, along with a brand-new, but promising detective, Leire Castro.

Leire Castro is the one who first notices some anomalies in the scene of Marc's death, and as she and Hector investigate further, they learn more and more about the dark underbelly of some of Barcelona's most influential families, both past and present. Does Marc's death have something to do with the death of a young girl years ago, at the summer camp where she and Marc were friends?

When Doctor Omar disappears and his office is found spattered with human blood, with a pig's head on his desk, Hector is under suspicion and must hope that his colleagues can solve that case before Hector loses his job and more.

Hill gives us a long look inside some aspects of Barcelona that tourists don't see. There is the world of privilege, but also human trafficking, child and spousal abuse, drugs. And we see that all those smiling Barcelona residents can also be extremely prejudiced, against South Americans, women, Africans.

Author Hill has a keen eye, and his plotting was ambitious, but his storytelling skills need a lot of work. This is where the book could have used a firmer editorial hand. Hill tells the story from the points of view of many different characters, which just didn't work. It gave the book a disjointed, uneven feel, and undoubtedly contributed to the lack of depth the characters have. It's hard to develop a character when the story's point of view changes frequently. He spends quite a bit of ink on some fairly minor characters, for no apparent purpose.

The writing is unclear, with it being too often difficult to tell which character is being referred to. There are also some sloppy errors, like a character owing 4,000 Euros in one chapter, which inexplicably becomes 3,000 Euros a few chapters later.

What bothered me more, though was that Hill also has a writing tic that became annoying fast. He makes a mysterious statement, which he then explains shortly afterward. But he uses this device constantly and about the most mundane things. For example, he drops the names Ruth and Guillermo, leaving the reader wondering who they are, then explains later on the page. Similarly, he has a character make a cryptic comment about her parents having a reason to disapprove of her current partner even more more than her old one, then tells why a few sentences later. This whole telegraphing technique, which I imagine was supposed to give an air of mystery to the book, just become a tiresomely overused device.

While Hector Salgado and Leire Castro are promising characters, their promise went unrealized in this novel.

Cormoran Strike, illegitimate son of a famous 70s rocker, veteran of the Afghan conflict who lost part of a leg there, is camping out in his office at his private detective agency. It's quiet there, since he has only one client, but there is plenty of mail and telephone contact, what with all the creditors dunning him.

Cormoran Strike, illegitimate son of a famous 70s rocker, veteran of the Afghan conflict who lost part of a leg there, is camping out in his office at his private detective agency. It's quiet there, since he has only one client, but there is plenty of mail and telephone contact, what with all the creditors dunning him.Cormoran is camping out in his office because he's finally broken things off with his fiancée, Charlotte, with whom he's always had a volatile relationship. The black eye she left him with as a parting gift evidences that. Cormoran and Charlotte were always an odd couple anyway; she with her classic good looks and upper crust background, and he with a OD'd groupie mother and the physique of a rugby player or club bouncer.

Speaking of bouncing, that's what Cormoran does when he rushes out of his office one morning and slams straight into Robin Ellacott, his new temp-agency secretary. Despite that violent introduction, Cormoran's battered face and the sleeping bag and camp bed in his office, Robin wants to stay on the job rather than get a permanent--and better paying--position.

Robin is intrigued by the idea of detective work, all the more so when, on her very first day, Cormoran's client ranks double. The new client is the brother of supermodel Lula Landry, who fell to her death from her Mayfair penthouse. The police concluded that her death was a suicide, but her brother is convinced otherwise. And, as Cormoran and his (new) trusty sidekick, Robin, investigate, they come around to the same point of view.

The investigation takes the pair into the hothouse world of the super-rich: models, designers, musicians, actors, film producers and many, many hangers-on. It's a world of such constant and casual falsity that it's hard to find out what really happened in the last days of Lula's life. Her family life is another rich vein of users and liars. But Cormoran and Robin are doggedly persistent, peeling off the layers of lies until the sad and ugly truth is finally revealed.

By now, everyone knows that "Robert Galbraith" is really J. K. Rowling. I picked up the book because I wanted to see how she'd do with my favorite genre, British mystery, but I quickly forgot all about that as I became engrossed in this story, and especially the principal characters. Cormoran and Robin are thoroughly developed and engaging personalities. Their personal stories unwind throughout the book, and I was left hoping to meet them again in a future book.

Would I have guessed the book was written by J. K. Rowling? I suppose the protagonist's name, "Cormoran," the same as a folkloric Cornish giant, should have been a clue to the author's identity, since Rowling is so well-known for her cleverness in naming characters. But that's about the only clue I might have noticed. Otherwise, it just seemed like a well-written British detective story; somewhat similar in style to writers like Reginald Hill and Peter Lovesey. My only significant criticism is that it bogged down at times, and it could have lost about 10-20% of those 464 pages to tighten it up. In particular, the solution to the whodunnit was so complex that it required too much exposition. I would like to see something more toward the "fair play" style of mystery, and I think Rowling is capable of that.

Recommended for fans of traditional British detective stories translated to the present.

2

2